Fans of American pulp horror cinema mourn the loss of George A Romero, leaving us after 78 years after a mercifully brief battle with lung cancer. In his early years, Romero went to Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh and stayed there after he graduated, making shorts and TV documentaries, scraping together the cash to make a breakout film – “Night of the Flesh Eaters”.

It’s a black and white 35mm horror story – a satellite radiation leak causes corpses to rise from the dead and devour the living. A potent combination of 60s Cold War paranoia – with isolation and alienation from the outside world turned mindless. Ben, the heroic main character of the film – played by a skilled Black actor Duane Jones – is murdered in the film’s finale, not by the shambling flesh-eating ghouls, but by scared white survivors. An almost unfathomable ending in 1968, and still daring to this day.

It’s a black and white 35mm horror story – a satellite radiation leak causes corpses to rise from the dead and devour the living. A potent combination of 60s Cold War paranoia – with isolation and alienation from the outside world turned mindless. Ben, the heroic main character of the film – played by a skilled Black actor Duane Jones – is murdered in the film’s finale, not by the shambling flesh-eating ghouls, but by scared white survivors. An almost unfathomable ending in 1968, and still daring to this day.

Due to a paperwork filing error, the retitled “Night of the Living Dead” fell out of copyright, and is now available for anyone to screen, print, colourise with computers and reproduce in animation. Of all these cursory imitations, the original is the best.

There are few modern social ailments that Romero’s zombie stories cannot recast, symbolise, satirise and fight back from. No fewer than five Living Dead sequels followed, with “Dawn of the Dead” delving deeply into American consumerism and “Day of the Dead” the military industrial complex. But it is 2005’s “Land of the Dead” which rattles around in my head to this day. It is among the finest American satires of foreign policy I have ever seen, and a cleverly structured parable of class consciousness and revolution.

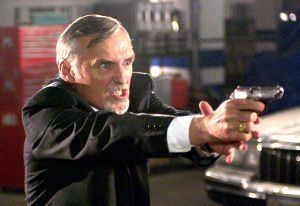

In Land, the dead have overrun the earth. Some of the last surviving humans live in a small city, protected by electrified fences, heavily armed soldiers and river moats. It is run by Kaufman (Dennis Hopper), a CEO-like arch-capitalist borrowing from the Dick Cheney foreign policy playbook. Kaufman runs a skyscraper city within a city, Fiddler’s Green, where only the elite and super-rich are permitted to stay. The rest of the human population live below on the streets, slaving away and dreaming of a better life.

In Land, the dead have overrun the earth. Some of the last surviving humans live in a small city, protected by electrified fences, heavily armed soldiers and river moats. It is run by Kaufman (Dennis Hopper), a CEO-like arch-capitalist borrowing from the Dick Cheney foreign policy playbook. Kaufman runs a skyscraper city within a city, Fiddler’s Green, where only the elite and super-rich are permitted to stay. The rest of the human population live below on the streets, slaving away and dreaming of a better life.

The imperialist Kaufman sends out heavily armed supply vehicles to seize food, medicine and black market goods from the rest of the zombified land. “If you can drink it, shoot it up, fuck it or gamble it – he owns it”. A 70ft long armoured truck, named Dead Reckoning, provides firepower, cover and support for the raiders.

Cholo (John Leguizamo), the head of Kaufman’s raiders, saves enough money to have a living within Fiddler’s Green – but gets spurned. Enraged, Cholo steals Dead Reckoning and holds the skyscraper to ransom. Kaufman announces, “We don’t negotiate with terrorists”; Cholo fires back with: “I’m gonna do a Jihad on his ass.”

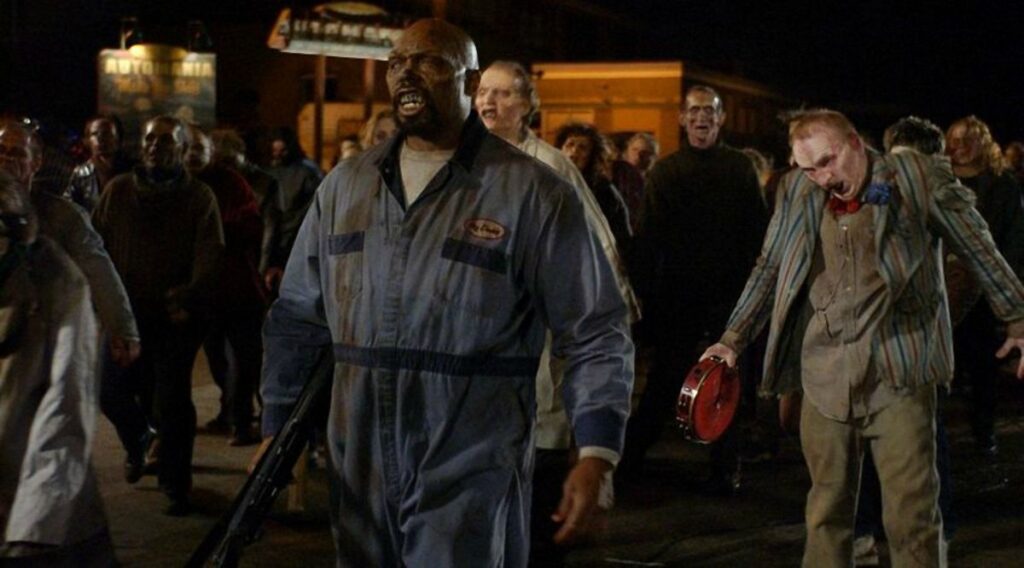

All the while, the dead begin their own self-aware revolution, led by Big Daddy (Eugene Clark). Who teaches others like him to communicate and work together to seize Fiddler’s Green for themselves. They arm themselves. They overcome social and physical barriers. They strike back with improvised weapons. They become aware – learning to ignore distractions by the materialist fortress.

This is gloriously fertile ground for social commentary, with the tripartite classes of humanity squaring off against each other. Avoiding the trap of simply scribbling the subtext in the margins, Romero thickly spreads Land of the Dead’s Marxist overtones with helpings of wry laughs and squeamish gore. Hopper is beautifully cast, delivering an engaging nasty performance as the venal leader with fingers in every pie.

George A Romero is among my favourite filmmakers. Along with expertly staged schlock, he brought provocation and wry social commentary to vivid American cinematic nightmares. A working class Bronx movie brat, raised on the British post-war cinema of Powell and Pressburger. When Romero brought “Land of the Dead” to the Edinburgh International Film Festival in 2005, the festival were screening a retrospective of Michael Powell’s work – complete with a new Technicolor print of Romero’s favourite film “The Tales of Hoffmann”. In conversation, his eyes, framed by gigantic milk-bottle glasses, shined at the prospect.

Popular radical cinema has lost one of its giants, and most provocative creators. His ideas and stories live on, free from the flesh. Tuck in.

Leave a Reply